Resource Library

Ask the Survey Doctor: How do you understand normality?

Insights | Series II | No. 6 | September 2014

Q. “Restoring normality” is a key task for assistance providers in post-conflict environments as well as for those working in counter-insurgency or disaster zones. It’s particularly difficult to assess and decide priorities as well as to measure progress in such places. Yet how do you measure “normality”? And what metrics can we use to do it?

A. Normality is a key goal of conflict resolution and humanitarian efforts – and like any other development goal, it needs to be monitored and evaluated. As Michael O’Hanlon and Jason Campbell have written, “The experience of successful counterinsurgency and stabilization missions leads us to place a premium on tracking trends in the daily lives of typical citizens.” Political and counter-insurgency theory suggests that satisfaction with living conditions boosts public support for governments – and data back this up.

But measuring normality is a challenge. The basic concept is hard to pin down. Moreover, levels of development and expectations vary drastically, and the areas of concern may be difficult or impossible for outsiders to access. However, solutions to this problem can be found.

As with other development objectives, the key to measuring normality is to operationalize it, that is, to define it in specific terms that can be assessed. This is a challenge we faced in our work in Pakistan, when we were conducting the first scientific surveys ever in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) on the Afghan border, where decades of war have devastated the infrastructure, and in the country’s settled areas, as we tried to assess quality of life.

In a conflict-plagued environment, we established a “normality index” based on a minimal definition of normality, focused on whether goods were circulating and the most basic of services operating. Thus our survey asked FATA residents about the functioning of markets, schools, clinics, and hospitals in their areas.

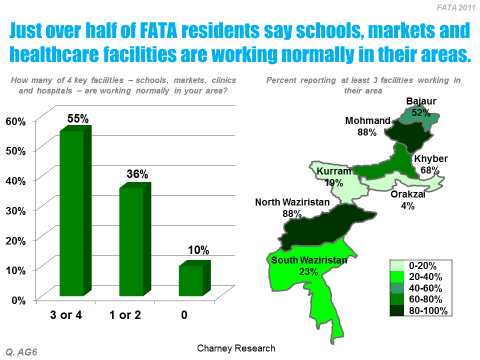

The results were revealing. (See Chart 1.) After major security force operations in parts of the tribal territories, 55% said at least three of the four facilities were working in their areas when we polled in 2011. Just over one-third (36%) said only one or two of the facilities were operating, while 10% said none were open.

We learned even more when we mapped the results (or for those fond of technical jargon, did geospatial analysis). There were two areas where almost everyone said most services were working – Mohmand, where the Pakistani Army had largely driven out the Taliban, and North Waziristan, where Taliban control was almost uncontested then. (Recently the Pakistan military has moved into North Waziristan.)

In contrast, service provision was least normal in the areas where conflict was most intense: South Waziristan, in the aftermath of a big Pakistan Army offensive, and Orakzai and Kurram, straddling a major Taliban infiltration route into Afghanistan. In these areas, few reported basic services were operating.

These differences had big political implications. In focus groups with FATA residents, we learned that when markets and infrastructure came back to life, hope returned to their areas, and their views on where their communities were headed improved markedly. On the other hand, those living among chaos were despondent – and skeptical of any authorities.

But normality implies more than the mere existence of services: it also means that people feel they are getting satisfactory service. Expectations increasingly involve quality and continuity of service. This is particularly true in areas above the most basic developmental level, as is true in most of Pakistan’s “settled areas” outside the FATA. If electricity is provided only six hours a day, for example, as was the case in much of the country when we were working there, people are unlikely to be happy with the service they are getting. This will carry over to the service provider – in this case, government.

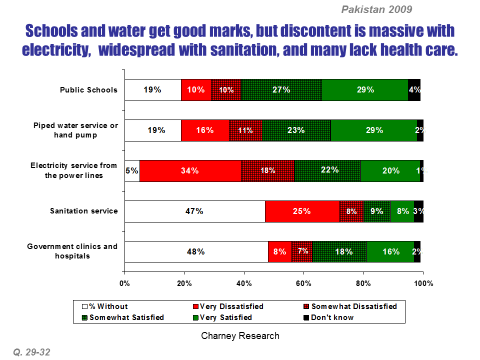

So we created a “service delivery index” to rate both provision and satisfaction nationwide with five essential services: schools, water, electricity, sanitation, and health care. In Pakistan, for example, we saw that provision of schooling and water was pretty widespread and the majority of the public was content with both. On the other hand, while electricity service was near-universal in the settled areas, the majority of Pakistanis were dissatisfied (due to those power cuts). Sanitation service was available to only half the public and even most of those were unhappy with it. On the other hand, the main complaint about clinics was that many people lacked them; those who had them in their areas were mostly happy with them. Overall, quite a mixed picture.

Once again, differences in service delivery mattered. When we looked at their relationships to other factors, we found service delivery among the most important influences on how people rated their economic circumstances. That, in turn, was by far the most powerful and consistent influence on Pakistanis’ ratings of government.

In other words, efforts to restore normality and strengthen services can be measured – and what’s more, they count. Getting the basic conditions of life back are enormously important to people. And they are likely to give their loyalty to those who can give these to them.